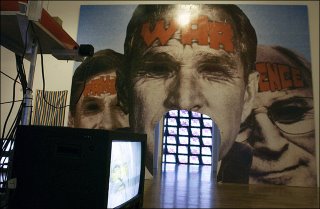

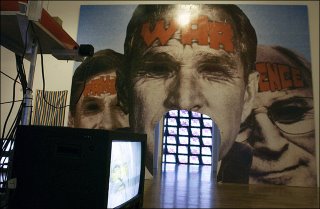

Oh, no! Another picture of Guernica!

An interesting non-argument was happening over on

Edward Winkleman about

Frank Furedi the nature of politics and art, and this is to perhaps overstate the case, but it sounds overly binary over there... either you are making political art, or you are making fluffy crap that only serves the purpose of pandering to the elite Chelsea Machine.

And don't get me wrong, I see the reason behind this drive to want political art. The number one subject matter rolling through Chelsea is

still a listless longing for each individual artist's teenage years, and that, when you look at what is going on in the world around you, is so head-in-the-sand, so not-getting-it, that it's embarassing. Sometimes I do wonder if artists are blind, and I wonder why I make art, and I wonder whether there is a social role for artists that makes more sense...

(sincerest apologies to

Ashes,

HLIB,

Art Powerlines for dragging them into my argument with

Eric Larsen about this by taking their thoughts about this out of context)

...And we know that Larsen is totally opposed to this idea, and he has a really cogent argument about why that is morally decent and logically true. To make political art that takes a side is to decide what good is for others, and in a "free democracy" this should be a matter of individual, empirical decision-making, an act of group participation, not a matter of indoctrination. To make political art is to decide what is "good" for other people, and that is tricky business because what "good" means shifts radically from culture to culture. The Greeks thought slavery was good,

Kat pointed out to me yesterday. And we live in a culture that uses the Greek Model for many things, including our (ailing) democracy, and yet we are capable of understanding that people who are not landowners should have a vote, for example, or that slavery is not good.

We have made these distinctions based on empirical evidence--we can perceive and therefore test our assumption that non-landowners use governmental services and can therefore logically deduce that these citizens should be active in governmental decision-making.

So what is a moral creature who can't handle this culture of

"truthiness", the coup of 2000, our unelected government, denial of empiricical evidence of climate change, shameless pandering to corporate interests and the total disappearance of the middle class to do? While I buy Larsen's assertion that to politicize art is to flatten it, and while the last thing I want to do is to join the idiocy and tell people what "good" is, I cannot stand here in my art tower and passively watch.

Larsen believes that there is no such thing as a social role for the artist as such--that the artist is no different from any citizen. And I think this conclusion is precious and backward-looking, that it is based on a firm wish that this would all just go away. I think there is something specific about being an artist that can be extremely helpful right now, and it has nothing to do with collapsing into political art, which is part of the problem, no matter how well-intended it might be. Larsen wants things to be as they were, and this is impossible.

I had a really good conversation with an artist who's working at Socrates yesterday. And yeah, I promised that I would never write about the park, but this isn't about the park. We were talking about the state of the world and what could be done about it.

Charles Ray, Unpainted Sculpture

See, artists are still trained to perceive the world around them and solve problems.

Less and less, sure, but you can be hot right now and be engaged in a perception project, like Charles Ray or Jennifer Pastor or this park artist, who I will name if he says it's cool. Or a makerthinker project. Or some other kind of empirically-based inquiry of the world around you that depends on figuring out how materials actually behave, what the world really looks like, what it really feels like to see the world, that membrane between raw data and what gets perceived by the mind, what it means. And this work can be as overtly political as Jon Kessler's

Palace at 4am or as absurd as Charles Ray's

Family or as physical as Streb. This dependence on probing the world empirically is still happening, even in a world of

Frank. Let's cling to this truth!

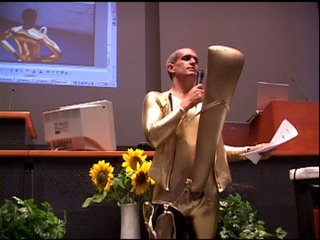

Jon Kessler, Palace at 4am

Stay tuned for a thorough treatment of why this sustained looking, this refusal to be soothed, this looking past and understanding of Larsen's media aesthetic, this continual need to dream by solving problems is the most powerful political act one can be engaged in, and why I think there is a specific social role for the artist as empiricist, as perceiver, as

makerthinker. It doesn't mean campaigning in the streets, or painting kid's faces, or even Art Powerlines' Art For The People. It's not Marxist, it doesn't require a revolution. It just requires making some good fucking art and being a part of a community that is willing to tell one another the truth about the empirical, perceptual importance and impact of work. That community can push out a whole culture of looking, a whole culture of problem-solving that does more than look backwards and long for what it was.

This kind of artmaking is elitist. It's more important than popular culture. It takes more time and you get more out of it, and that's okay. In fact, it's critical.

The most political thing an artist can do right now is create something that requires, elicits and rewards sustained viewing, that celebrates problem solving. This is true because the only things to do to a culture of lies are to find and expand what is not a lie, and examine and understand the lies thoroughly.