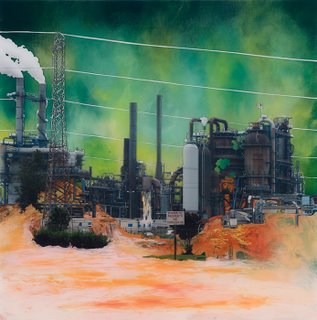

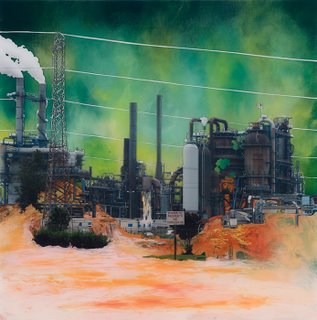

Greetings

Greetings, 2006. All images courtesy

Caren Golden Fine ArtIf you have a chance to see this work in person today, it's worth the trip. In fact, I am sorry that I did not get it together to write about Castellanos' work sooner. See, they are very strange things, these photocollages Castellanos has created. Images of them don't do the work justice--they look like badly photoshoped images of

Williamsburg and

Nature when in fact they are the opposite of that.

This is not easy work. The images themselves are not sexy. They are a little too romantic, a little hackneyed. And somehow this becomes okay... or even more than okay. This becomes the point. The images are made in a very weird and thoughtful way, and so become a narrative of their making as much as they become images of things.

Castellanos makes photocollages--he starts with intricately hand-cut large-format photographs. This defiling of the photograph with scissors is satisfying because it's so much easier to do this in a non-committal way, in photoshop, for free, with infinite capacity for do-overs. It's a gesture of Castellanos' commitment, but then he commits himself further. These shreds of photograph are then painstakingly mounted on masonite or some other kind of board, and then made part of an oil painting.

That's right. Thick-n'-gooey, slow-drying, frustratingly amorphous oil paint has to contend with the crispness and the total flimsiness of the photograph. This is done in layers, with a coat of resin freezing in each layer of work. The result is a fattish wedge of image that you can look at from the side and decode a little bit.

And you want to spend time decoding this work. Perhaps decode is the wrong word. Above all else, this process reads as about its own improbability, the sense that it really should not work. This turns each photocollage into a Don Quixote story of its making, with clunky, difficult passages that are redeemed by areas of transcendent effortlessness. You wind up trusting Castellanos' craft to guide you into a very slow looking session. Looking at how, looking at the junction between things, looking at decisions.

Of course the strangest part about this work is that you are left with an image that you are very invested in, having looked at the how of making it, but that does not thrill... yet. Castellanos is after something very difficult--these pieces should utterly fail, and it is their near failure that makes them intriguing.

This failure and its constant overcoming is meaningful when we look out on so much that is failing or threatening to fail. It's this flirtation with failure that could get pushed into someplace we haven't been before. I trust Castellanos to take me there, but he's not yet.

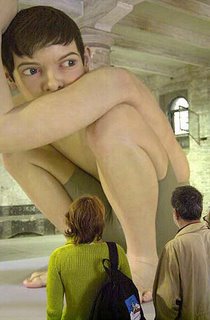

Breach

Breach, 2006

Chelsea is a very safe place right now--artists are making fewer truly dangerous choices and often have no recognizable relationship to failure. Castellanos is a brave stand-out in a digitized, professionally fabricated, easy-to-describe scene... but of course he is human. There are safe choices in

Deadland that need to be mentioned because the work's meaning seems to be a function of its riskiness. I like the romantic imagery--it reads as daring when it works, more evidence of the artist's commitment. It's Rockmanesque. But Castellanos' reliance on the scale, composition and logic of the original photograph seems like an arbitrary limitation. And I hope to see a much more fucked up paint-to-photograph relationship in the future. Of course I am biased, but I want more mistakes, more calamity. More redemption. More like

Breach, above, and less like the landscape work, which tends to be easier, more paint-by-numbers.

But what I really want is to see more of this work soon. It's generous and committed, and could explode into something truly thrilling.