Segue To MakerThinker: Fuck Despair

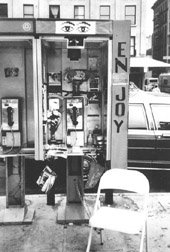

Sophie Calle's Phone Booth

I listened to an interview with Morris Berman on Media Matters last night, and came to understand why I have been indulging in all this Chicken Littleism, and also came to understand why this attention to Berman and Larsen is an indulgence, and why they are, respectfully, wrong.

And I know that I promise myself never to write about the Park, but I can't get my point across any other way. (I am both rusty and hip-deep in the next show's installation...)

See, if Larsen and Berman were asked to install a sculpture at Socrates, they would probably claim that it is impossible, because they know what it takes to install a sculpture and the conditions are simply insufficient! The grant is not quite enough to actually make a sculpture. The city surrounding the park ensures that your sculpture will get lost in a sea of scale-fuck and look diminutive. The ground is impossible to dig in because it used to be a landfill. There is no real labor to help you, but the park is open all the time, so while you won't get any help digging, you will get plenty of dogs stealing your gloves, babies wandering up to you while you are jackhammering and folks asking questions. The wind comes off the water and will blow your sculpture over in the winter unless you engineer it right. It always seems to rain for many days straight right before an installation deadline. The park doesn't drain at all (as it is full of cement), and so your pants will soak up rainwater for days after the rain stops. The place is impossible.

And yet, if you go to the park anytime this week, you will see evidence of twenty people managing to pull off really cool stuff. These people are not throwing up their hands and calling it impossible! They are working with what is there, making a sculpture with the money allotted or finding more, learning how to use the jackhammer, thinking about the wind, braving the rain. They are also paying their rent this month, eating well enough, holding down jobs, keeping the rest of their opportunities flowin', and managing to have a good time, even though working out there sucks when it's hot, and sucks even more when it's wet. The adverse conditions of the park inform their work, kick their asses, and bring out both the best and the worst in folks, but nobody has ever failed. Nobody has ever not put up a sculpture in twenty years.

In other words, the park may seem impossible, but that sense of impossibility is never the last word. It always evolves into something else.

Berman and Larsen see the world and America's relationship to it as impossible. And they are not wrong because they see something that is untrue. The undergraduate's relationship to study has changed drastically since I graduated ten years ago, and not for the better. The world does look less reality-based every day. We are still cooking the planet. Bush is actually reading The Stranger this summer, and this does not make everyone who read this book in high school go find their copy and pelt him with it.

Berman and Larsen see what we all see. But it is arrogant to assume that failure is inevitable. It's also too easy. And the only purposes this line of thinking can serve are conservative.

Working at the park is the best thing that ever happened to me because it is such a free-for-all. Because it is a space where anything can and does happen. Against all odds. With too little money and too little muscle and too few tools. It is a beautiful place because it shouldn't even be there, and working in it shouldn't work. And yet it does, and the whys and hows of this become more mysterious to me, not less, the longer I work there.

This mystery is deeply, profoundly true. I never understood before I started working in the park that not knowing can be divinely empowering. You never know how things are going to go until you actually put your hands on it and get busy. An idea can fail. But once it starts being actualized--once the idea becomes a series of tasks or negotiations--then true utter failure is impossible because the process itself is so incremental. To fail is to not try.

Okay, okay. But Berman and Larsen are talking about all of society and not about one park or one sculpture. And well, all I can say is that it's easier to decry the dirtiness of the whole city or the whole world than it is to clean one's own house. I was walking regularly in Bed-Stuy last year, and saw the power of the individual in full force. I would walk down a bleak patch, and then one spring day one lady cleaned up her stoop and put some flowers out and a sign that said "No Litter" and started sitting out there. Started saying good afternoon. This simple, individual act transformed the street over the year. The immediate area stopped being such a good place for high-school kids to behave badly. Other folks lingered longer to talk story. What was a bleak, sketchy stretch of my walk started being my favorite part. Lots of hellos. More flowers. More clean stoops. More community.

This woman's simple act was infectious, and there was no external reason for her to have any hope that it would work. And if she was reading Berman or Larsen, she might have turned herself inward and denied her community what she had to offer. The Monastic Option is essentially misanthropic, as is declaring that everyone born after a certain date has less cognitive ability than older folks. It is turning away from a larger society and working in a vaccuum, and the projects that come from that vaccuum are going to be, necessarily, backward-looking and not particularly useful or pertinent to the rest of society.

Listen, I am just as angry with what I see as Berman and Larsen are. But to yield to that despair is indulgent and denies what I know to be true. I can't look at the whole world in terms of turning away from it anymore. I just want to be the woman on the stoop. I just want to face my community with my hands dirty and see what happens next.