Studio shot--trying to figure out how big you can make something out of paint.

I don't want to inadvertently write a manifesto, so I'll start with a confession. My back was troubling me this weekend, and so I spent most of Sunday stoned and doodling while watching

Brokeback Mountain over and over again. And the movie got so stupid that I downloaded someone reading the short story from Audible and just kept going, with the movie on and the sound turned down and the real story playing on headphones, drawing bad humpy landscapes out of hunched shoulders and stands of fir trees and the hindquarters of sheep moving downhill. And while there is certainly nothing sexier than cowboys in love, I wasn't sure what I was doing with all this. I blamed being really stoned and not wanting to get up off the heating pad.

I might be making excuses for laying around all day, but I think I learned something. Before my body revolted on Sunday morning, I was working on a really egotistical, manifesto-ey tract about political art and what it's good for and what kind of political art I am making. It was prompted by a discussion on

The Intrepid Art Collector, and it was full of proclamations about things like what I want Kara Walker to do and why

Steve Mumford is not, IMO, making good political art. Fate seemed to intervene, and I want to tell someone about it, even if it doesn't make much sense. Because I don't want to make political art.

Let's jump off Politics Bridge: The story Proulx wrote is not political. It's not about being gay. It's about being human. It's about Ennis' missed opportunity and Jack's reaching out for something impossible and this freaky little bubble of hope that they pushed out between them, this fat space in such a lean world, and how impossible it was to do that and how the electricity between them demanded an accommodation and how tenuous Jack and Ennis made that accommodation, even though it was the single most important thing to them as individuals.

The reason the movie is completely retarded (although watching Jake Gyllenhall and Heath Ledger

do it is great fun and the cinematography is lovely) is that it makes them gay. It makes them flirt before they even know one another's names. It makes them pretty boys and not buck-toothed, cave-chested losers who are so poor they can't afford socks. All this gay-ifying, complete with families that one must come out to or not, makes it all political, with hurt feelings all around and a moral at the end of the story that dovetails nicely with whatever PFLAG is saying these days. Every puritanical and tidy impulse to make this freakishly unique story

about something that is easy to understand was followed. The result is so moralistic--

this could all just be avoided, and life just isn't like that.

Proulx, I am sure, has political ideas about gay rights, but she didn't write a gay story--she wrote a love story in which the kind of love served as this perfect device to talk about manliness and loss. The west is all about manliness and loss. As a westerner, I love the way she took this very specific love affair and turned it into a prism through which the existential problem of the west (you are totally empowered by all this space and utterly enslaved by it at the same time) shines and turns into its parts: poverty, brutal jobs and brutal weather, lonliness, conservatism, individualism.

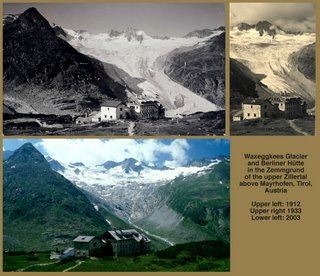

I am not as disciplined an artist as Proulx. I rush to the finish line and want quick understanding, quick answers. I get into political discussions on this blog and others and in my art because I am afraid of what I chose to examine. My desire to solve the problem of climate change gets in the way of just seeing it for what it is. Climate change is a fantastic device for drawing out our most supreme arrogance and most intense fear. My work does not come close to touching that yet. That human state is beyond politics. Maybe if I admit to all thirty of you that this is what I am after, then I will find the courage to go out and look for it.